Tax-Loss Harvesting: Why You Shouldn’t Wait Until December

While December is the last month to take care of any last-minute tax issues, tax-loss harvesting shouldn't be one of them.

Anything you read about it being “tax-loss harvesting season” is either marketing drivel, ignorance by the author, or laziness on the part of your financial advisor.

Here's the truth: Your tax-loss harvesting should be done when prices are at their lowest point of the year, regardless of what month it is.

Sometimes that's in December, but most of the time it's not.

Here's everything you need to know to get the most out of your tax-loss harvesting, and why you shouldn't wait until December to do it.

Key points

- Tax-loss harvesting is the process of selling investments at a loss to reduce your tax liability.

- Regularly harvesting losses can lead to significant tax savings each year and is one of the most effective ways to boost after-tax returns.

- Most people wait until December to tax-loss harvest. They shouldn't.

What is tax-loss harvesting?

Not every investment you make will turn out to be a winner.

While no one likes losing money on an investment, these losing positions do come with a small benefit: you may be able to use them to offset some of your tax liability.

This is known as tax-loss harvesting (TLH).

Here's how it works:

- You sell an underperforming position and “lock in” the loss.

- You use that loss to offset some of your tax liability, either from capital gains or taxable income.

- You re-invest the proceeds from the sale in a different investment with similar characteristics.

Yes, your investment still lost money — TLH doesn't fix that. But at least you can use those losses to reduce your tax bill.

Regularly harvesting losses and reinvesting the proceeds can lead to significant tax savings over your lifetime and is one of the most effective ways to boost your after-tax returns.

An example of tax-loss harvesting

Tax-loss harvesting can offset capital gains and, if your losses are greater than your gains, some taxable income.

To see how this all works, consider this example:

- You own a position in Apple (AAPL) and it's down $15,000.

- You have sold several profitable investments (in your taxable brokerage account) throughout the year (all short-term) for a cumulative gain of $8,000.

- You're married, make $100,000 in ordinary taxable income from your job, and you're subject to a 30% tax rate.

Because your losses are larger than your capital gains, the remaining losses can offset up to $3,000 of your regular taxable income ($1,500 for married couples filing separately).

Any amount over the limit can be carried forward to offset taxes in future years.

You know you can use TLH to offset some of your tax liability, so here's what you do:

- You sell your Apple position and lock-in the $15,000 loss.

- You re-invest the proceeds from the Apple position into QQQ.

When it comes time to pay your taxes, how much did you save?

Your $15,000 loss offsets all of your short-term capital gains for the year, with $7,000 left over.

Since you're married, you can apply another $3,000 to reduce your ordinary taxable income. You then carry forward the remaining $4,000 to offset income in future years.

Congratulations. You just saved yourself $3,300.

The math

Your loss on Apple ($15,000) covered all of your capital gains ($8,000) which, because they were short-term gains, you would have owed your ordinary income tax rate (30%).

You saved $2,400 ($8,000 x 30%) there.

You were also able to use another $3,000 to reduce your ordinary taxable income from $100,000 to $97,000, another savings of $900 ($3,000 x 30%).

And, you have another $4,000 being carried forward, meaning that it can be applied in the future.

While the concept of tax-loss harvesting is straightforward, because of its effectiveness at reducing your tax burden, the IRS has set limits on what income TLH can be used to offset and rules on what constitutes legal tax-loss harvesting.

TLH: IRS rules and other considerations

Here are some important considerations to keep in mind when tax-loss harvesting:

- Tax-loss harvesting only works in taxable accounts. You cannot deduct losses generated in a tax-advantaged account, such as a 401(k) or IRA.

- Long-term losses are initially offset against long-term gains, and short-term losses are first used to offset short-term gains. Any leftover losses in one category can be used to reduce gains in the other category.

- If your capital losses are greater than your capital gains, you can use the extra losses to offset up to $3,000 ($1,500 for married couples filing separately) of your ordinary taxable income.

- Tax-loss harvesting is more beneficial for people in higher tax brackets and those with short-term losses.

- When reinvesting the proceeds, you must follow the wash-sale rule, which states that if you sell a security at a loss but repurchase the same or a “substantially identical” security within 30 days before or after the sale, the loss cannot be claimed to lower your taxable income.

What is a "substantially identical" security?

The IRS has not provided a straightforward definition of what constitutes a “substantially identical” security. It's up to investors to use their best judgment to avoid the wash-sale rule.

For example, selling SPY and replacing it with VOO would trigger the wash-sale rule and disqualify your tax-loss harvesting. However, you could replace SPY with an ETF tracking another market, such as the Russell 1000 (IWB).

Though probably ok, selling Apple and buying Microsoft would fall in the grey area of the wash sale rule.

For more information on wash sales, see pages 84-85 of IRS Publication 550.

Now, with all of that groundwork laid, here's why you shouldn't wait until December to do your tax-loss harvesting.

The problem with tax-loss harvesting in December

As mentioned in the introduction, most people take care of any last-minute tax issues for the year in December, including tax-loss harvesting.

However, if your objective is to secure the largest losses possible (which it should be), you want to sell your losers when prices are at their lowest point of the year, regardless of what month it is.

The problem with waiting until December to TLH is that prices might not be anywhere near their lowest point.

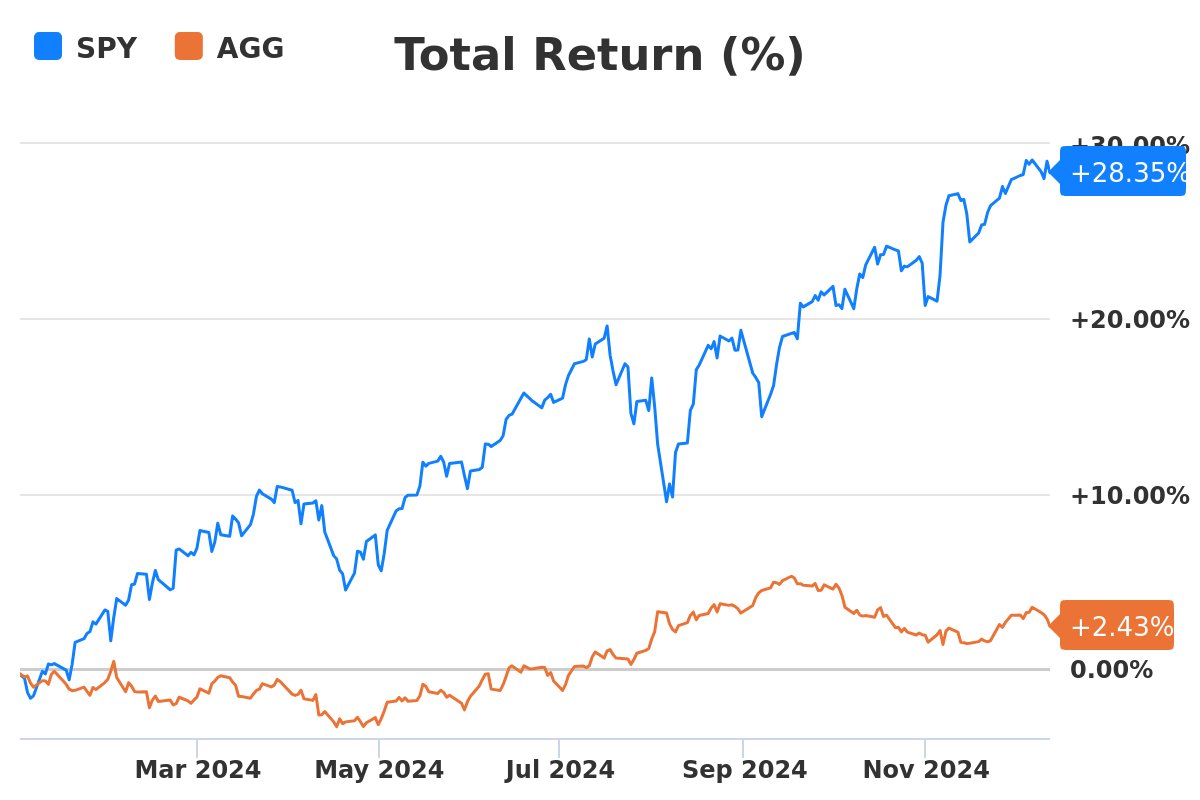

Just look at this year:

Source: Stock Analysis

Stock prices (SPY, the S&P — the blue line) are at their highest point of the year.

While there may be opportunities for TLH within your portfolio, broadly speaking, December is the worst time for harvesting losses in all of 2024.

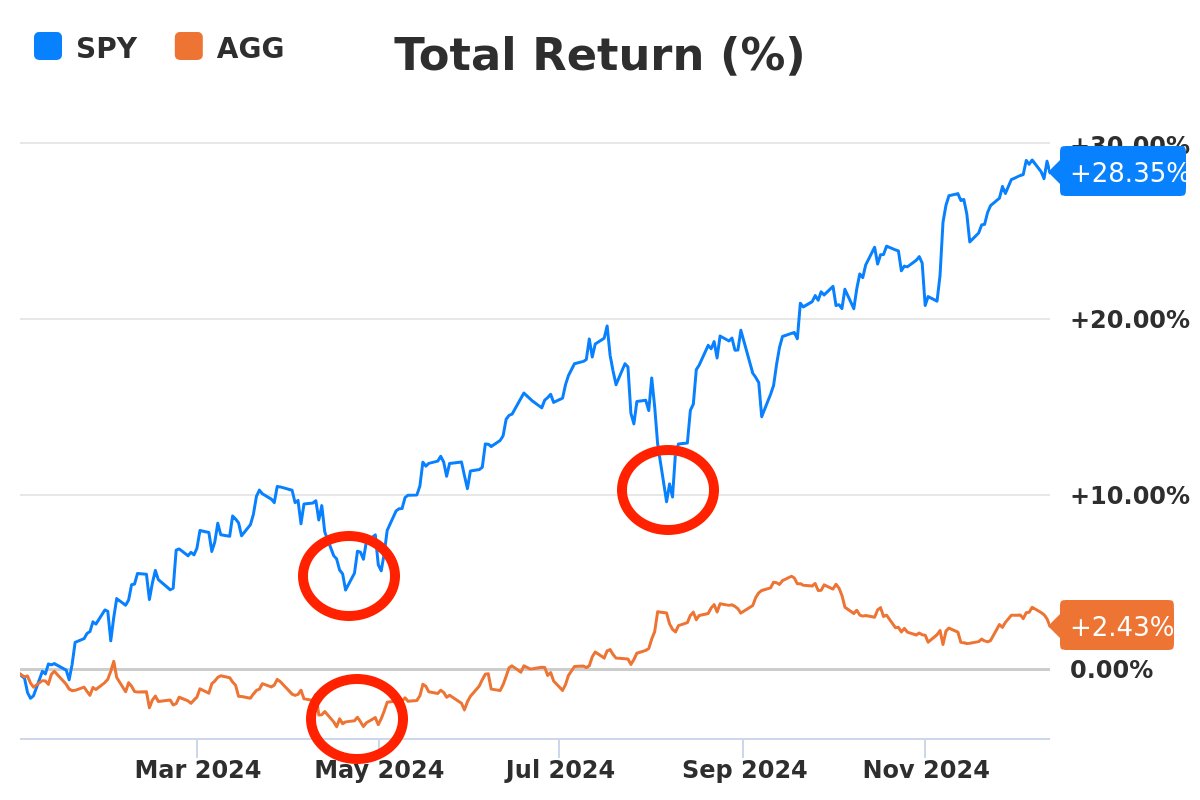

In 2024, mid-April and the beginning of August were the best times to harvest losses:

Source: Stock Analysis

Similarly, while bonds (AGG, iShares Core U.S. Aggregate Bond ETF — the orange line) aren't quite at their high for the year, they're not far off from it either. Late April was the best time for harvesting bond losses.

Learn about the differences between investing in individual bonds vs bond funds.

As you can see, 2024 is a perfect example of why you shouldn't wait until December to do your tax-loss harvesting.

If you wait until December, as most people do every year, you will have missed the best time the overwhelming majority of the time.

Even if you do have losing positions in December, chances are you would have had more losing positions at a different point in the year and the losses would have been more severe. That's when you should have been tax-loss harvesting.

How do you know when you should be tax-loss harvesting?

Admittedly, we can only identify the lowest prices of the year in hindsight.

In December, it's easy to look back at the year and say April was the best time for TLH, but that wasn't obvious in April. In April, we had no idea where the markets would move next.

So, what's the answer? When should you be tax-loss harvesting?

Since we can't time the markets, there's no “right” answer to this question. It can't be answered scientifically.

Here's my rule: Be opportunistic about harvesting losses throughout the year. If the market drops 10%, look for losing positions to sell and replicate with similar (though not too similar) positions. Do it again every time the market falls another 5%.

No, I don't get the timing perfectly right. I almost never sell my positions exactly at the bottom.

But, by following this process, I almost always capture more of the losses than I would have had I waited until December each year.

Final thoughts

While I'm hesitant to tell you to trade your portfolio when markets feel the most dire, those are the most valuable times for TLH.

Very rarely, if ever, does this equate to waiting until December to do all of your tax-loss harvesting for the year.

If you do decide to harvest losses, be sure to use the cash to replicate your former positions' market exposure.

Otherwise, you drift into trying to time the markets, which is one of the surest ways to lower your returns.