The Simple Truth About What Causes Inflation

Inflation surged in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Many of the top economists, academics, and financial journalists blamed the increasing prices on supply chain disruptions, Russia's war in Ukraine, tight labor markets, and loose consumer spending.

They called the inflation “transitory,” saying it would dissipate once businesses reopened and life got back to normal.

It was a popular narrative. But it was incomplete.

That's why, three years later, inflation remains stubbornly high.

What those economists' line of thinking overlooked is that inflation — on a macro scale — can only be caused by one thing: too much money chasing too few goods.*

As you'll read in the sections below, this isn't possible without an increase in the money supply.**

*This school of thought is known as monetarism. It was developed by Milton Friedman, who won the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976 for his theories on the role of money in inflation.

**That is, the Federal Reserve printing money.

Here's everything you need to know about what inflation is, what causes it, why the Fed targets 2% inflation, and how raising interest rates combats inflation.

What is inflation?

Before getting into what causes it, let's quickly break down what inflation is — and what it isn't.

Inflation is the rate at which the aggregate price of goods and services increases over time.

Inflation is an increase in the general level of prices, not an increase in the price of an individual good. A price increase in an individual good — like eggs, rent, or gas — may be a symptom of inflation, but it is not inflation itself.*

*This is a common misconception and an important distinction.

Inflation can also be thought of as the devaluation of money, which means money saved today will be worth less in the future. If inflation is running at 2%, $100 today will be worth $98 a year from now.

What causes inflation?

As mentioned in the introduction, some economists blamed the post-COVID increase in prices on things like supply chain disruptions and rising labor costs.

These are specific cases of what is commonly known as “cost-push” inflation.

Cost-push inflation occurs when the prices of goods and services increase due to increased production costs, like higher wages or raw material costs.

In turn, this increase in costs forces businesses to raise their prices to maintain their profit margins. Prices are “pushed” upwards.

While the theory of cost-push inflation makes sense intuitively, some critics have discredited it for failing to consider broader macroeconomic principles.

Prices of individual goods and the general level of prices are two different things:

- Prices of goods: Prices of individual goods are a microeconomic phenomenon. They are determined by a number of factors, including the cost to produce the good. Supply chain disruptions or rising wages that increase the cost to produce the good often lead to an increase in the price of the good.

- General level of prices: The general level of prices is a macroeconomic phenomenon. It is determined by the total supply of money relative to the total output of goods and services (GDP). Only a change in the money supply relative to GDP can cause the general level of prices to change.

Inflation is the increase in the general level of prices. And the only way for the general level of prices to increase persistently is by increasing the money supply faster than the growth in GDP.

An increase in the price of an individual good may be a symptom of inflation, but it — by itself — is not inflation.

An example will make this more clear.

Example: where inflation comes from

Say an entire economy consists of 10 apples, 10 oranges, and $30. Each apple is worth $2 and each orange is worth $1.

Now let's say the apple farmers form a union and increase their wages by 50%. To reflect the increase in costs, the apple company increases the cost of an apple to $2.50.

There are still 10 apples and 10 oranges produced. But because there is still just $30 to spend, now consumers must decide how to allocate their resources.

Let's say the demand for apples stays unchanged despite the price increase — all 10 are sold for a total of $25. That leaves just $5 left to buy oranges.

Since demand has fallen, the orange company drops its prices to $0.50 per orange.

This is how macroeconomics works.

If the money supply doesn't increase, any increase in spending on a certain good or service (apples) will be offset by a decline in demand for all other goods (oranges). The prices of those goods will fall, leaving the general level of prices unchanged.

If supply chains are disrupted or higher labor costs lead to an increase in prices for certain goods or services but the money supply doesn't increase, consumers are forced to change their spending patterns.

When prices for certain goods rise, consumers buy less — either less of the good itself or fewer of its alternatives. Upward pressure in some areas is offset by downward pressure in other areas. There simply isn't enough money to go around.

But if the money supply is increased, things change.

Continuing with our example from above, let's say the money supply increased to $40 when apple prices were raised to $2.50.

All 10 apples are sold for a total cost of $25, leaving $15 left to spend on 10 oranges. The oranges can now sell for $1.50 each.

In this scenario, the prices of all goods rose because there was more money in the economy. (However, it should be noted that this is a simplified example.)

When the supply of money increases faster than the increase in total output, prices must rise. Or, as Milton Friedman put it, inflation is “too much money chasing too few goods.”*

*This is known as “demand-pull” inflation.

Why is inflation high right now?

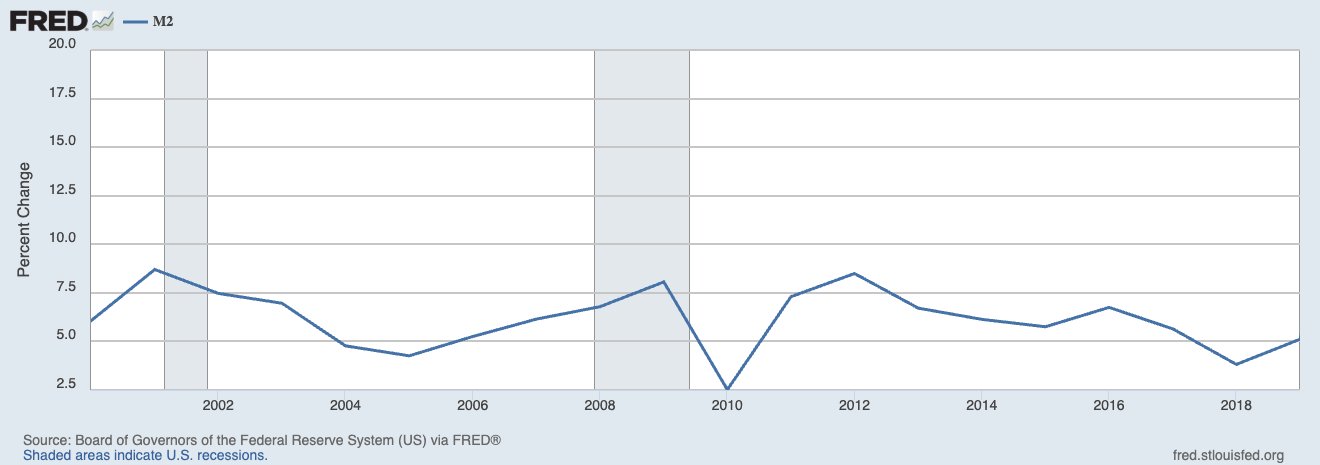

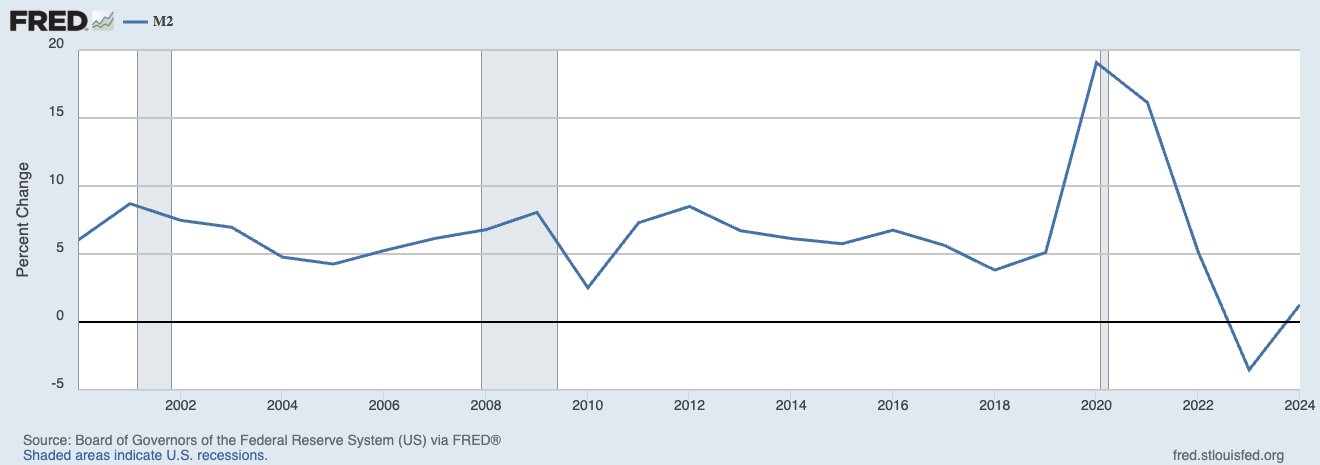

From 2000 to 2019, the U.S. money supply increased* at an average annual rate of 6.2%:

Source: Fred

*The Federal Reserve increases the money supply by printing money and using it to buy long-term government bonds or other assets.

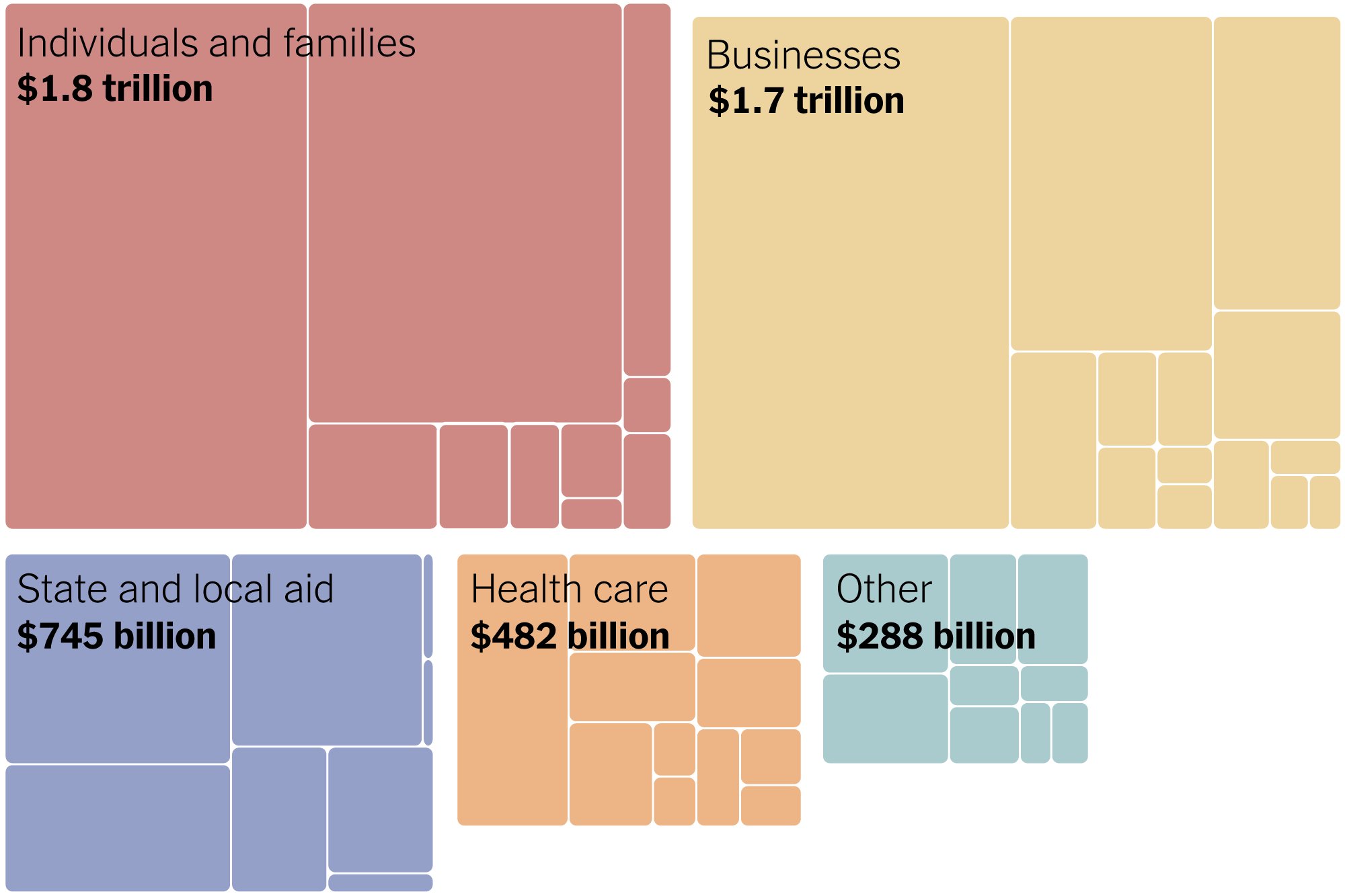

In 2020, in response to the COVID-19 shutdowns and to stave off a potential recession, the Federal Reserve printed and injected $5 trillion into the economy.

This money went to consumers, small businesses, and other industries in the form of stimulus checks and forgivable loans. Here's the breakdown:

Source: New York Times

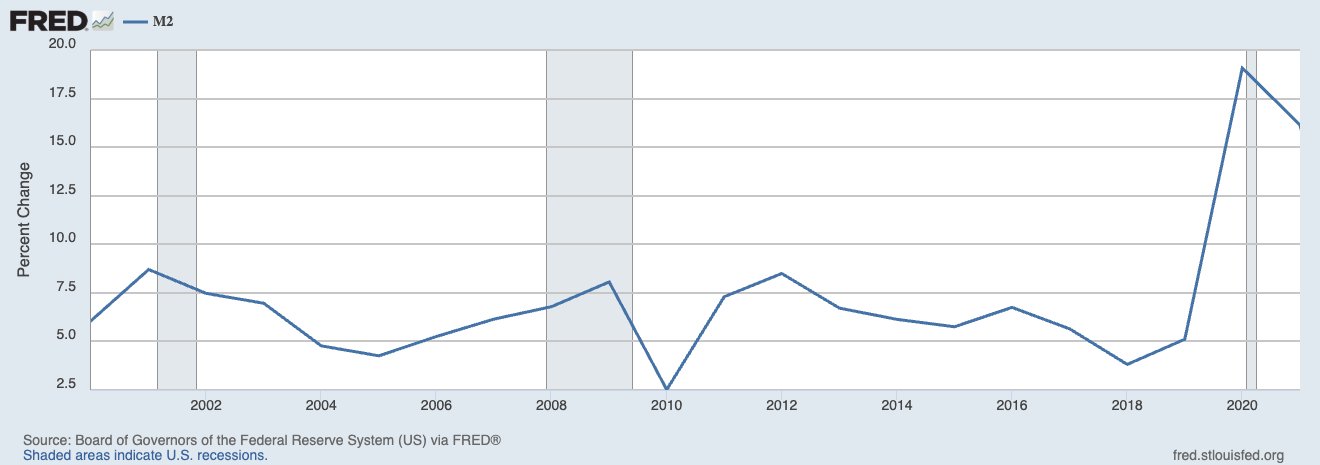

This $5 trillion stimulus package was primarily deployed in 2020 and 2021, increasing the money supply by 25.7% in 2020 and another 11.4% in 2021.

Source: Fred

In total, between February 2020 and February 2022, the U.S. money supply increased by 40.7%.

While the injection worked to keep the economy out of a recession, it came with inflationary consequences.

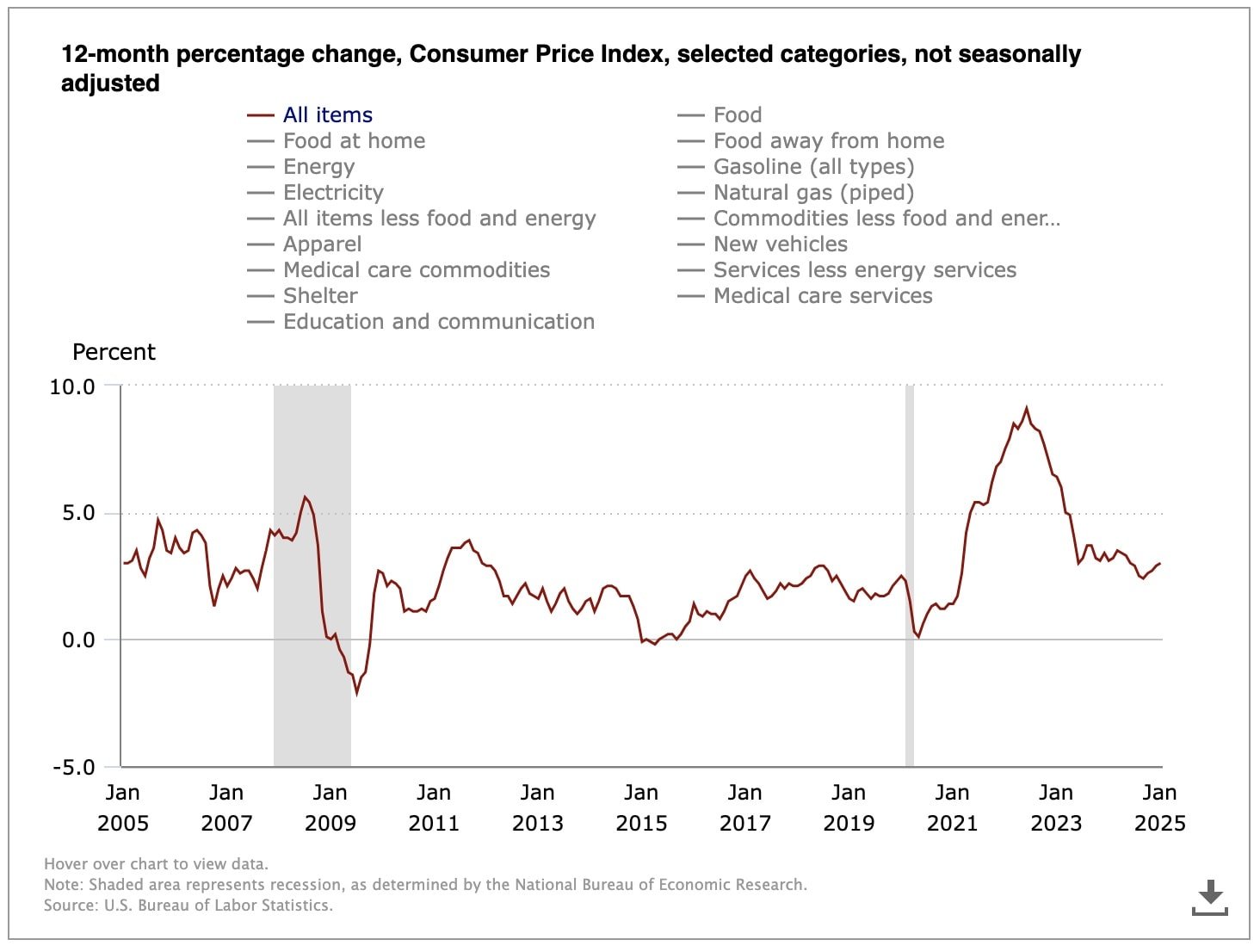

Inflation shot up from around 2.5% in December 2019 to over 9% by June 2022:

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

This inflationary response makes sense, as there was 40% more money in circulation and no increase in production.

Since people had more money to spend, demand increased, but supply stayed the same. There was too much money chasing too few goods.

When this happens, prices can only go in one direction: up.

Why does the Federal Reserve target 2% inflation?

The Federal Reserve (the Fed) has two goals (known as its dual mandate) for fostering a stable and growing economy:

- Promoting maximum employment, as defined as a long-term “normal” unemployment rate of 4.1%.

- Promoting price stability, as defined by an annual inflation rate of 2%, measured by the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) index.

The Fed targets a 2% inflation rate because it believes that supports long-term economic stability. Here's how:

- Avoids deflation: Deflation (falling prices) encourages people to delay spending, which slows economic growth. The best way to avoid deflation is to create a small amount of inflation.

- Stabilizes prices: A stable inflation rate makes it easier for people to make informed decisions about spending, saving, and investing. Too much inflation can erode purchasing power, sporadic inflation can create uncertainty, and deflation can slow economic progress.

- Encourages investment: Businesses and individual investors will invest excess cash to protect their purchasing power, which encourages economic growth.

- Increases wage growth: A small amount of inflation helps employers increase wages steadily over time which improves living standards and reduces unemployment.

- Provides monetary policy flexibility: A 2% target gives the Fed room to lower interest rates when needed to stimulate the economy during downturns and recessions.

The 2% target was established in 2012 after a decades-long deliberation.

It isn't fixed or magical, but its proponents believe this rate supports economic growth and minimizes risks like runaway inflation or deflation.

How does raising interest rates combat inflation?

The Federal Reserve uses interest rates to influence the economy.

When inflation is high, the Fed may raise interest rates, which makes borrowing less attractive for businesses and consumers. This decreases the demand for goods and services which, in turn, slows the economy.

The Fed's main tool for influencing interest rates is the Federal Funds Rate, the interest rate it pays to banks on their reserves.

Pay a high enough rate and banks won't bother making external loans. When the Fed talks about “raising rates,” this is the rate it's referring to.

However, to really combat inflation, the Fed needs to reduce the rate at which it adds to the money supply by printing less money, something it's been (quietly) doing:*

*The graph below shows the growth in the money supply, which now needs to stay below the long-term average of 5–6% per year for the economy to "soak up" the extra money.

Source: Fred

So yes, raising interest rates will slow down the economy.

But if the goal is to curb inflation, what the economy really needs is time to soak up the extra money that was created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, if the economic data begins to show signs of a slowdown, the Fed has indicated that it's unlikely to respond by lowering interest rates, and may opt to increase the money supply instead.

If it increases the money supply too much, stagflation (a combination of high inflation, stagnant economic growth, and high unemployment) may become a problem.

To know where inflation is headed next, keep an eye on the money supply.