Direct Indexing: What It Is, How It Works, and Why It’s Overrated

Direct indexing is an investment approach where an investor buys all of the individual stocks that make up an index rather than buying a fund that tracks the index.

The idea is that the portfolio's performance will be identical, but because each stock is owned individually, the investor will have more losing positions which can be “harvested” each year.

This can add up to a significant amount of tax savings, especially for high earners.

However, while direct indexing sounds great in theory, it's rarely useful. In fact, for most investors, direct indexing produces lower after-tax returns than simply owning the index fund.

Here's everything you need to know about direct indexing — including what most people don't know about it — and how to decide whether it's worth it for you.

What is direct indexing, and how does it work?

You're probably familiar with index funds, where in one investment you can own a basket of securities that track a given benchmark, like the S&P 500 or the Russell 3000.

By contrast, direct indexing (also known as personalized indexing or custom indexing) involves buying all of the individual companies that make up an index.

For example, instead of buying Vanguard's S&P 500 ETF (VOO), you would buy the 500 stocks that make up the S&P, in the same proportions as they are weighted in the index.

This strategy produces nearly identical returns as owning the ETF, but because you own each stock individually, you could greatly increase your portfolio's tax efficiency and customizability.

Here's how.

How direct indexing enables tax loss harvesting

The primary benefit of direct indexing is that it enables more opportunities for tax-loss harvesting.

Tax-loss harvesting is the process of selling investments that have lost money to offset taxable investment gains or ordinary income. You can read more about it in this article.

If you own a portfolio of index funds, your options for harvesting losses are limited to those funds.

Direct indexing, on the other hand, allows you to drill down to the individual stocks within each of those funds.

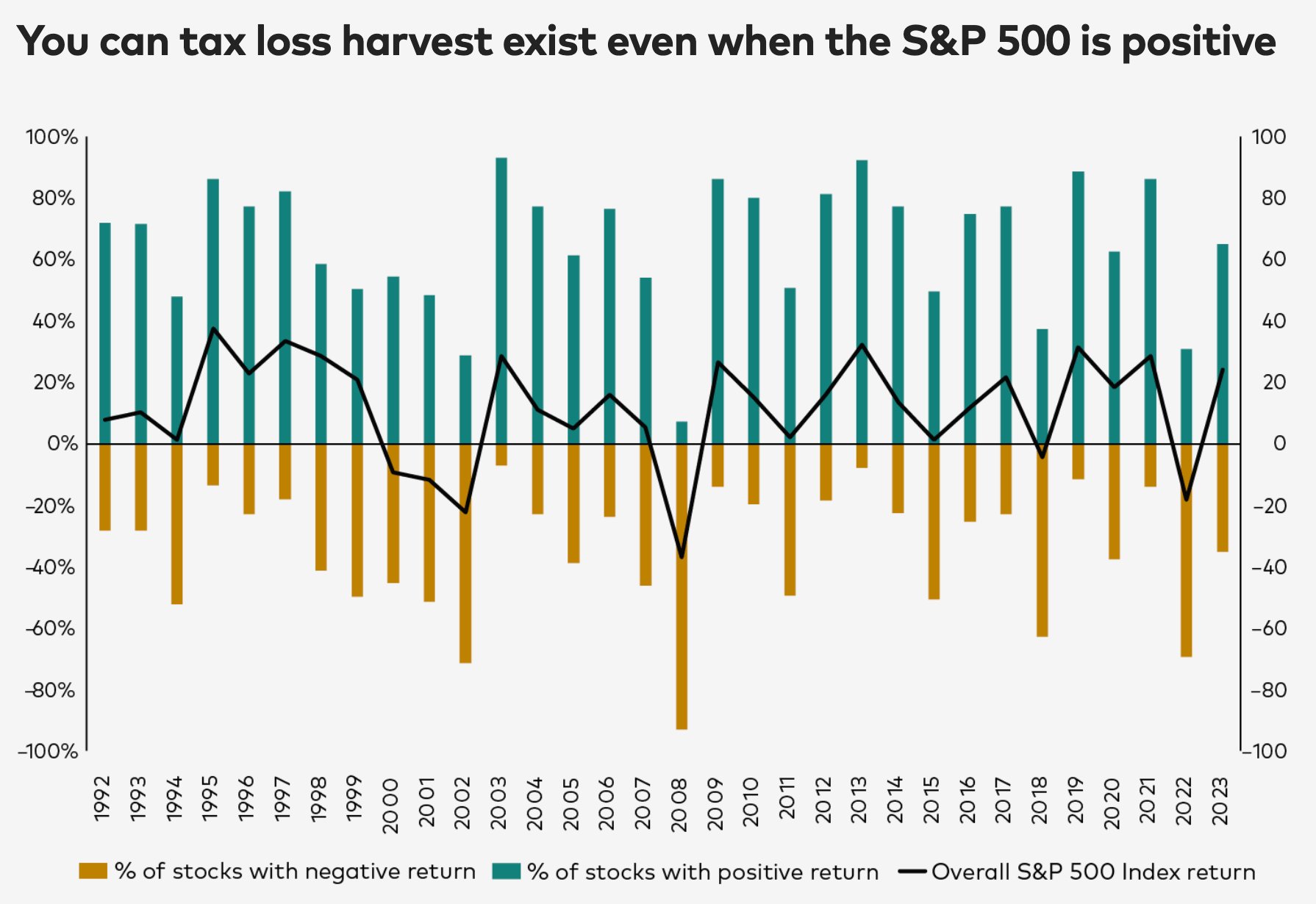

Because you own each stock individually, you're almost certain to have losing positions, which can be harvested to reduce your tax liability. This is true even in years when the index's overall return is positive.

Source: FactSet

In 2023, for example, the S&P returned over 26% but only 65% of stocks had a positive return.

- If you had bought VOO at the beginning of the year, there would be no losses to harvest at the end of the year.

- If you had direct indexed the S&P 500 at the beginning of the year, ~35% of the stocks you owned could be harvested at year's end.

What can you do with these losses?

Harvested losses can be used to offset capital gains and then up to $3,000 of ordinary taxable income. Losses can also be carried forward to future years.

For example, a high earner with $100,000 worth of gains in a taxable brokerage account may have a combination of losing positions that add up to $50,000 in losses.

By selling these losing positions (“harvesting” their losses), this person can reduce their tax liability from $35,000 to $17,500 (assuming a 35% tax rate).

While harvesting losses can significantly lower your tax bill, there are three often-overlooked reasons why direct indexing is unsuitable for most investors.

Why most investors shouldn't use direct indexing

As we've already seen, unbundling an ETF opens opportunities for tax loss harvesting, which can have a material impact on after-tax returns.

And, as you'll read below, it also enables an extremely granular level of customization.

However, despite some obvious benefits, direct indexing is not that useful for most investors for three primary reasons.

If any of these are applicable to you, you can stop reading. You shouldn't bother with direct indexing.

1. Most people aren't using taxable brokerage accounts

The primary benefit of direct indexing is having more opportunities for harvesting losses, but most investors have the bulk of their investments in retirement accounts.

Retirement accounts — like 401(k)s and IRAs — are tax-advantaged, which means gains and losses do not affect your annual tax liability.

For this reason, there's no need to harvest losses in these accounts.

Tax-loss harvesting only works in taxable brokerage accounts, which is the last place most investors make contributions.

In 2026, you can contribute up to $24,500 to a 401(k) and $7,500 to an IRA. Most investors fill these accounts first, and only the extra (if any) flows into a taxable account.

And, even if you do place some money into a taxable account, you'd need to be investing a significant amount before direct indexing's tax benefits would amount to anything meaningful.

2. Most people aren't making regular, sizable contributions

Many investors focus on the initial tax savings of direct indexing, without considering how the strategy plays out in the years that follow.

Since stocks generally increase in value over time, one problem that can arise with systematically harvesting losses is that, after a few years, you will have sold all the losing stocks in your portfolio.

At that point, you'll be left with hundreds of winners with low cost bases, and no room for tax-loss harvesting.

For this reason, direct indexing works best for investors making ongoing contributions. Since tax-loss harvesting can be done at the individual lot level, new purchases create fresh opportunities to harvest losses in the future.*

*New money usually goes toward underweight stocks to re-align your portfolio with the index's proportions.

Not only should you be making regular contributions, but the contributions need to be quite large.

To illustrate this point, here's a breakdown of the potential tax savings from direct indexing based on annual contributions of $50,000 vs $10,000:

| Annual contribution | $50,000 | $10,000 |

| Estimated harvestable losses (7.5%) | $3,750 | $750 |

| Tax savings (24% tax bracket) | $900 | $180 |

Most people need to invest at least $50,000* per year into a taxable brokerage account for direct indexing to generate enough tax-loss harvesting benefits to justify the higher cost and complexity.

*Remember, this is in addition to the $30,500 you likely contributed to retirement accounts.

3. Most people don't want the huge mess direct indexing causes

Direct indexing sounds exciting until you realize you've turned your simple index fund into a chaotic portfolio of hundreds of individual stocks*.

*Worth noting, research shows you can also replicate the S&P 500 with a sampling of well-selected stocks, or around 100 positions instead of the full 500. Other research found it can be done with as few as 27 positions.

Owning a lot of stocks means many moving parts, and opens the door for tracking error — this is when a hand-built portfolio's returns start to differ from those of the index it's tracking.

For example, your returns may start to drift from the index you're mirroring because tax-loss harvesting and wash-sale rules* force you to hold different stocks or weights than the index.

*The wash-sale rule states that if you sell a stock or security at a loss, you cannot repurchase the same or an essentially identical investment within 30 days before or after the sale date, or the IRS will disallow the loss for tax purposes.

It's also a recipe for complexity. You will have an ever-expanding list of individual lots to track, making tax preparation complicated and portfolio changes harder to execute.

Over time, you can end up with an immovable portfolio full of low-cost-basis winners that would trigger huge capital gains if you tried to sell.

Once you start direct indexing, it can be extremely hard (and expensive) to unwind.

It also used to be quite time-consuming, but some brokerages (like Fidelity, Schwab, and Frec) now offer automated direct indexing services, so this is no longer an issue. More on these services below.

The bottom line? Direct indexing does not provide material benefits for most investors and does not warrant the time, effort, and complexity it entails.

Who should use direct indexing?

While not worthwhile for the average investor, direct indexing may be beneficial for people who match the following criteria:

1. High-income, high-net-worth investors

If you're in a high tax bracket and have a large taxable portfolio, tax-loss harvesting may save you enough money to outweigh the hassle and administrative costs that come with direct indexing.

Additionally, you should be earning enough to make substantial contributions to your taxable accounts each year, or you will likely run out of harvestable losses after about three years.

With enough new money coming in ($50,000+ a year is a common threshold), there should always be fresh positions that could be harvested later on.

2. People who don't mind added the complexity

Even if you're making large enough contributions to your taxable accounts to warrant direct indexing, your portfolio will consist of hundreds of positions, each with multiple lots and cost bases.

This can add a lot of complexity.

While there's software that can automatically look for harvesting opportunities and rebalance your portfolio (more on these below), you will have to pay for it. And these fees eat into your tax savings.

Plus, the software doesn't solve the visual clutter caused by owning so many positions, and will likely make it worse.

Furthermore, since selling your positions will trigger large capital gains, you should be comfortable with holding your sprawling portfolio until you reach retirement.

What effective direct indexing looks like

Here's a scenario where direct indexing is useful.

John is in the 35% tax bracket. After maxing out all of his retirement accounts, he has an extra $5,000 per month to save.

John opens a direct indexing account and contributes the extra $5,000 per month to the account. Each new contribution gives him new tax lots for fresh harvesting opportunities.

He never sells winners and is very opportunistic with tax loss harvesting. The account experiences little tracking error and only trails the index by 0.20%.

Each year, he is able to harvest $4,000 in losses to offset income, saving him $1,400 in federal taxes.

In retirement, John uses the standard deduction and realizes portfolio gains up to the 12% tax bracket, effectively paying $0 tax.

By deferring* his taxes and planning his withdrawals, John has more than made up for the extra cost of direct indexing.

*Harvesting via direct indexing just delays when you pay taxes; it doesn't avoid them altogether (see this).

However, most high earners will be in a lower tax bracket when they retire (like John), so it's oftentimes worth it to push off paying taxes to a later date.

There's one other great reason for direct indexing, which I cover in the next section.

How direct indexing enhances portfolio customization

While the direct indexing strategy is best known for its tax advantages, it also gives investors greater control over their portfolios.

Since each position is owned individually, it's much easier for an investor to overweight or underweight certain holdings or sectors, or leave companies out of their portfolios altogether.

While most passive, index-fund-focused investors would take issue with this idea, it does make sense in certain circumstances.

For instance, a Google executive who receives stock options as part of their compensation may want to leave Alphabet stock out of their index.

They may also want to reduce their exposure to technology companies in general.

This can help reduce their net worth's correlation to the performance of one company.

Direct indexing providers

In the past, direct indexing required hundreds of transactions to replicate owning an index like the S&P 500.

It also required an investor to calculate exactly how many shares of each company in the index to buy, to manually harvest losses, and to regularly re-weight companies based on changes in market capitalizations.

For these reasons, institutional investors were the only ones with account balances high enough to justify the costs of implementing direct indexing.

But now, multiple brokerage firms and other companies have built direct indexing software that, among other things, automatically scans for tax-loss harvesting opportunities and performs scheduled rebalancing.

Here are a few of the most popular providers:

| Firm | Account name | Annual fee | Minimum |

| Fidelity | Managed FidFolios | 0.70% | $5,000 |

| Schwab | Personalized Investing | 0.40% | $100,000 |

| Frec | Frec Direct Indexing | 0.09% | $20,000 |

| Wealthfront | S&P 500 Direct | 0.09% | $5,000 |

This software, plus commission-free trading and fractional shares, has made direct indexing much more accessible to individual investors.

Final verdict

Direct indexing can be a powerful tax savings strategy, but only if you're:

- A high earner,

- Regularly making large contributions to a taxable brokerage account, and

- Not bothered by having 100+ individual positions.

For most people, one of those things generally isn't true, which is why direct indexing sounds good in theory but may not be that useful in reality.

However, if all of the above things are true, brokerages like Fidelity, Schwab, Frec, and Wealthfront make the process much easier.