Corporate Income Tax

Corporate income tax is the total tax that a company must pay on profits earned.

It's calculated by taking taxable income and multiplying it by the corporate tax rate, like so:

Corporate income tax = taxable income x corporate tax rate

Corporate income tax has a considerable impact on a business's cash flow. For this reason, corporations often develop complex strategies for reducing their tax liability.

Understanding how corporate income tax works, as well as its impact on a business, gives investors a sense of a company's ability to retain the profits it earns.

Below is a comprehensive overview of corporate income tax in the U.S. including rates, how it works, and how to calculate corporate income tax.

What is corporate income tax?

Corporate income tax is the percentage of profits a business must pay to the government.

Corporate profits consist of revenue minus the cost of goods sold (COGS), general and administrative expenses (G&A), depreciation, R&D, interest, and other operating costs.

In the U.S., the total corporate income tax collected by the government represents the third largest source of federal revenue. Put simply, corporate income tax represents an enormous sum of money and has a sizable impact on a company's finances (1).

Furthermore, the U.S. has both federal and state corporate income taxes.

The current U.S. federal corporate tax rate is 21%. This amount came into effect in 2018 after the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) was signed. Prior to this, the rate was 35%.

In addition to the 21% federal tax rate, 44 states and the District of Columbia (D.C.) levy state taxes on corporate income. The rate varies by state, with the lowest being a flat rate of 2.5% in North Carolina and the highest being a marginal rate of 9.8% in Minnesota (2).

In 2022, corporations paid an average combined tax rate of 26% (3).

SummaryCorporations must pay 21% of their profits to the federal government. In most cases, they must also pay an additional sum to the state in which they are incorporated.

How does corporate income tax work?

Any company in which the owners or shareholders are taxed separately from the business is classified as a C corporation and is subject to federal corporate income tax.

In 2022, the total corporate income tax collected from these businesses accounted for 8.7% of total federal revenue. In 2023, that number was 9% (3,4).

The current federal corporate tax rate of 21% is relatively low compared to previous periods in U.S. history. For example, the rate averaged more than 50% in the 1950s and 1960s (4).

Businesses not designated as C corporations are subject to different tax structures.

For example, S corporations, sole proprietorships, limited liability corporations, and partnerships are all known as pass-through businesses since they pass their profits through to the owners.

The benefit of pass-through corporations is that owners avoid the double taxation associated with C corporations — once at a corporate level and again at the shareholder level.

Owners in pass-through corporations pay taxes on profits according to the individual income tax code. Many businesses find this structure preferable and, in fact, net income from pass-through entities has increased greatly since 1980.

The rise of pass-through businesses may explain why corporate tax revenues represented an average of 4.2% of the GDP in the 1950s and 1960s but only 1.6% in 2023 (4).

As far as returns go, U.S. corporations are taxed on an annual basis. Companies must file tax returns on the 15th day of the 4th month following the close of a tax year, though in some cases, the federal government will grant the corporation a six-month filing extension.

Corporate tax filing is usually done with Form 1120, and nearly all companies are expected to pay their federal corporate income tax via four estimated payments.

Calendar-year companies must make payments on the 15th of April, June, September, and December. Fiscal-year corporations must make payments on the 15th day of the 4th, 6th, 9th, and 12th months of the tax year (5).

SummaryC corporations must pay federal income taxes, while businesses classified as pass-through entities are taxed according to the individual income tax code. Tax returns must be filed by the 15th day of the 4th month following the tax year's end.

How to calculate corporate income tax

The calculation for corporate income tax is:

Corporate income tax = taxable income x corporate tax rate

And here are the additional equations you'll need:

Taxable income = adjusted gross income minus all applicable deductions

And

Adjusted gross income = gross income minus all applicable adjustments

Example calculation

Consider a company with a net profit of $75 million and total allowable deductions of $5 million. Using the above formula, the company will pay a total of $14,700,000 in corporate income tax.

The math is calculated as follows, by first determining taxable income:

Taxable income = $75,000,000 - $5,000,000 = $70,000,000

And then calculating corporate income tax:

Corporate income tax = $70,000,000 x 21% = $14,700,000

Considerations

In a real-life setting, an international corporation is likely to pay far less than this amount because of strategic business practices. For example, they can place items like intellectual property in low-tax jurisdictions such as other countries that have lower tax rates.

Additionally, many corporations will take advantage of losses incurred by their subsidiaries. This strategy reduces their tax burden even further.

As examples, you can read here about a few dozen companies that paid no money in federal taxes on their 2020 profits (6).

SummaryCorporate income tax is calculated by taking taxable income and multiplying it by the corporate tax rate. However, it should be noted that businesses do not always end up paying the whole rate.

How do corporations use deductions?

Corporations can reduce their tax liability by deducting business expenditures that are necessary for the operation of the business.

Examples include salaries paid to employees, bonuses, healthcare benefits, and even tuition reimbursements.

Corporations have a long list of expenditures they can use, which may include:

- Legal services

- Insurance premiums

- Excise taxes

- Travel expenses

- Interest payments

- Tax preparation fees

- Bookkeeping

- Bad debts

- Sales taxes

- Advertising costs

- Fuel taxes

Note that this list is not exhaustive, and can vary by industry and business classification.

Part of the reason the U.S. tax code allows for tax expenditures is because, in some instances, these practices encourage innovation.

For example, tax credits for research and development might incentivize a company to allocate more money for exploring new technologies.

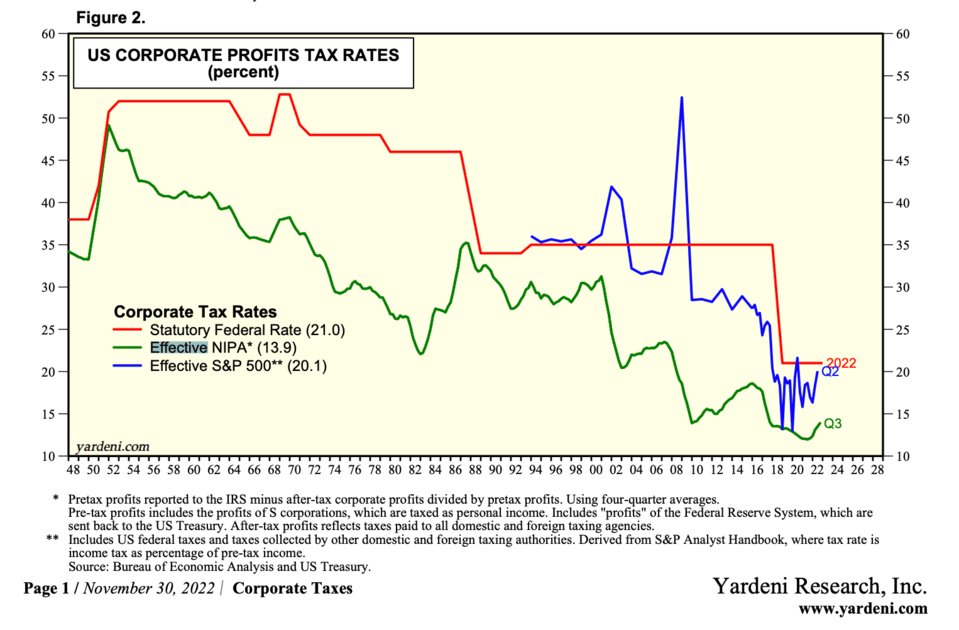

However, maximizing deductions is often a key focus for corporations. Often, what they end up paying — the effective tax rate — is much lower than the statutory rate (7).

You can see this in effect in the figure below:

Source: Yardeni Research

SummaryDeductions, known as tax expenditures, are a way for businesses to reduce their tax liability. These expenditures must be costs that are necessary for business operations.

How much do state tax rates vary?

State corporate income tax rates vary dramatically by state.

States like Washington, Texas, Ohio, and Nevada impose gross receipts taxes instead of corporate income taxes. These kinds of taxes are sometimes referred to as “turnover taxes.”

Gross receipts taxes are different from corporate income taxes because they apply to the business's sales without making any deductions for the business's costs.

This means that the taxable amount owed is not adjusted for expenses or profits. Moreover, gross receipts taxes also apply to all business-to-business transactions.

Businesses find this kind of tax especially burdensome because so much revenue is subject to taxation. In contrast, states like this structure because it generates considerable income.

Some states, like Wyoming and South Dakota, do not impose a state corporate income tax or a gross receipt tax. Meanwhile, states like Tennessee, Oregon, and Delaware impose both state corporate income tax and gross receipts tax.

More information on individual state tax rates can be found here.

Notably, as recently as 2024, many states have reduced their corporate tax rates.

SummaryState corporate income tax rates vary dramatically from state to state. Some states require no state corporate income tax, while others impose heavy taxes in the form of gross receipts tax, state corporate income tax, or both.

Pros and cons of corporate income taxes

A key benefit of corporate income taxes is that they provide a crucial source of revenue to the government. By taxing corporations, the state and federal governments are able to fund operations that allow public programs to exist.

A drawback of these taxes is that they might dissuade new businesses from forming if the rates become too high. Additionally, as tax rates increase, some businesses may be encouraged to move to more tax-friendly countries.

It's important to keep in mind though that other factors can affect why a company may want to operate in a certain jurisdiction, such as competition.

Research also suggests that increasing the federal corporate tax rate to 28%, up from its current level of 21%, would cause wages to fall by 1.27%.

This scenario would mean that a worker earning the U.S. median income of $52,000 could see a drop of $840 in their annual earnings (8).

However, lowering corporate income tax has a big impact on government revenues.

From 2000 to 2019, for example, U.S. corporate tax revenue as a share of GDP fell from 2.0% to 1.1%, which represents a loss of $200 billion in revenue for the government, according to data from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) (9).

Additional research from the CBPP shows that more than 80% of the extra cash received from the 2017 tax cuts went to buybacks and dividend payments, while only 4.6% went to research and development and 14.4% went to capital investments (9).

SummaryIncreasing tax rates may encourage U.S. corporations to relocate or discourage new business ventures. However, corporate income taxes fund critical public programs and the majority of cash from the 2017 tax cuts went to buybacks and dividends.

Corporate tax trends over time

As discussed earlier, corporate tax rates have declined dramatically over the past century, especially compared to the 1950s and 1960s, which averaged around 50% (4).

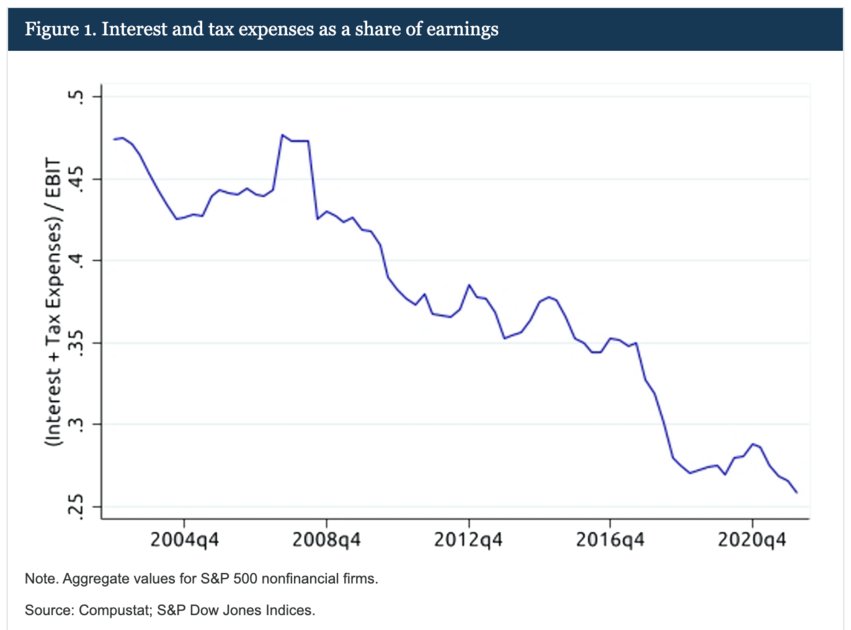

The Federal Reserve notes that over the past 15 or so years, for S&P 500 nonfinancial firms, taxes and interest costs have consistently decreased compared to earnings.

Before the financial crisis, the ratio of interest and taxes compared to EBIT was around 45%. By the end of Q1 2022, for example, it was 26%. Overall, a much smaller portion of profits is now being paid to tax authorities (10).

This can be seen in the chart below:

Source: The Federal Reserve

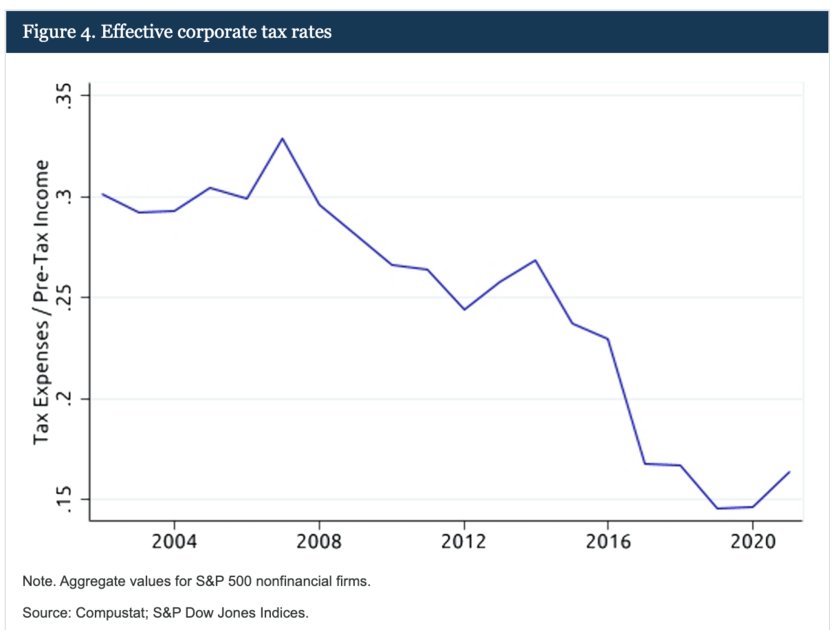

The report goes on to illustrate why this decline is happening, noting a critical factor was the drop in corporate interest rates, which can be analyzed by looking at the ratio of interest to debt.

In addition, the effective corporate tax rates also declined:

Source: The Federal Reserve

SummaryCorporate tax rates have decreased dramatically over the past century, with notable drops occurring in the 1980s and 2018. On the whole, a much smaller percentage of profits is now paid to tax authorities.

The takeaway

All U.S. businesses classified as C corporations must pay federal corporate income taxes on their profits. As of the time of publication, the federal tax rate is 21%.

Companies must also pay state corporate income tax, which varies considerably based on which state a business is incorporated in. These rates range from 2.5% to 9.8%.

Businesses often seek to maximize their tax incentives, which are the deductions they can subtract from their total taxes owed, or take advantage of other tax jurisdictions. In this way, they generally don't end up paying the full corporate income tax rate.

Notably, the degree to which corporate tax cuts help the economy is an open debate.

However, research shows that much of the money corporations saved from the most recent tax cuts was allocated to buybacks and dividend payments rather than capital expenditures.

And, on the whole, U.S. corporate tax rates have steadily decreased over time.